Five Deadly Innocent Media Mistakes Activists Make

Dimitar Sabev, Tax Justice Campaigner

Strict division of labor is a rather unusual phenomenon in the dynamic environment of non-governmental organizations. In my tax justice campaigning routine I used to make use of all of my knowledge and skills piled up during the last 15 years: university lecturer in marketing, financial editor, editor-in-chief, investigative journalist, terrain researcher in environmental economics, columnist, author of books – and maybe even more roles I am not aware of.

Writing entirely from my experience I would like to point out five zones where the NGO sector is challenged in understanding and working with the media.

The gravest and most widespread media mistake of activism is predictability. In many cases the media do not let you in, not because they are bad, biased, or bribed by the big evil businesses, but simply because you do not produce any news with your message. The public knows very well what to expect from you. “Multinationals are bad, ordinary people are poor, poor is good. Pay your tax, don’t smoke” – and the audience falls asleep.

There is a sense of predictability also in radical campaigning. The campaigning methods may be really creative, yet the pattern of most of the messages is too straightforward, and often contradicts the everyday experience of the general public.

To get into the minds of people you should really surprise them. To get into the news you should surprise the journalists. One does not have to run naked or climb smoking chimneys, it suffices to break stereotypes. I think I have done something like this before.

Taxdog, our tax justice campaigning blog, recently featured an article about an ordinary guy who is actually a tax evader. The hero of the story did not issue a tax receipt and was severely punished by the revenue agency. Meanwhile, in the same area, a huge multinational company had not been paying corporate taxes for a decade. Most probably the company had evaded hundreds of millions in corporate taxes, but operated totally undisturbed.

At first sight the story of our small businessman producing and selling fish was not so attractive: I retold it in a TV interview, there were several reposts in internet sites, and that was all. Yet it reached to people previously not supportive of the Tax Justice cause. They were really surprised that tax justice activists may humble their position acknowledging the fact that not paying taxes in some cases may be the only way to stay afloat in an unfair business environment.

At first sight the story of our small businessman producing and selling fish was not so attractive: I retold it in a TV interview, there were several reposts in internet sites, and that was all. Yet it reached to people previously not supportive of the Tax Justice cause. They were really surprised that tax justice activists may humble their position acknowledging the fact that not paying taxes in some cases may be the only way to stay afloat in an unfair business environment.

On the surface the morale of the story was “stop punishing the small business with taxes”. But some people got familiar also with the need for fairer taxation of big corporations. A week later we issued a more sophisticated article about the setbacks in the national taxation system – and the people already lured by the human story had to acknowledge that one thing leads to another.

Another example of how to surprise the media and public when campaigning on taxes is the sectoral approach. Instead of relating to abstract notions like taxes and justice in general, I use to amass data on corporate taxes payed by retail chains, breweries, mines, petrol stations, etc. People do not listen about percentages of GDP, but pay attention to tangible things like tomatoes, cigarettes, bier, gold, or timber. The self-identification with the cause gets much stronger.

The second problem zone is the timing. Here the major rule is to avoid competition, being the monopoly in the media time. From my own experience as an ordinary journalist I know that there are several short moments when all national media desperately needs news. One of them is the week between the tenth and fifteenth of September. The summer is over, but the politicians are just returning from holidays and have not produced anything yet.

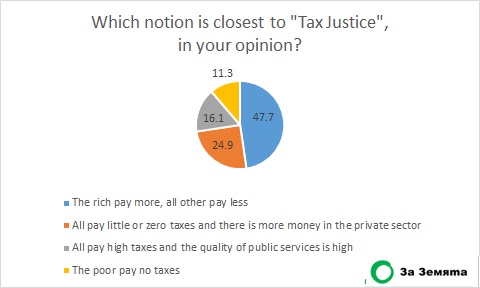

This year on 13th September we made a small round table where results from a nationally representative survey on tax attitudes were presented. In busy months like March or October such things would be covered briefly by some media ally. But in the acute deficiency of news in the mid-September the media coverage proceeded as an avalanche.

This year on 13th September we made a small round table where results from a nationally representative survey on tax attitudes were presented. In busy months like March or October such things would be covered briefly by some media ally. But in the acute deficiency of news in the mid-September the media coverage proceeded as an avalanche.

I gave one interview on the national radio in the morning, one on the telephone at noon, and another on the TV in the afternoon – and the interest continued for a whole week. Our tax survey was literary everywhere, being one of the three main news stories for the week. Because of the right timing we had a monopoly, albeit a brief one.

More or less, the same may happen in the hot summer months, or in the days following the big national holidays. It is true that at that time the audience is also thinner, but the very fact that an unpopular concept appears in a mainstream media makes it look more familiar, and more acceptable for the primetime at some later point.

This summer I and a colleague of mine “smuggled” into the biggest national TV broadcaster a 15 – minute story about the tax avoiding techniques of some of the biggest multinationals in Bulgaria. This was really a breakthrough, and even if someone missed the story in the hot August days, it circulated later on the Facebook.

The concerned corporations threatened to stop sending ads to this TV channel, but my colleague somehow escaped being punished. Some activists asked me later: “How much did you pay them?” Not a single cent, our TV appearance was due simply to right timing – and rare journalist bravery.

This leads to the third problem zone, namely – do activists really care about journalists that risk their jobs to produce a good and objective story? The activists’ points of view are not always welcomed and it happens that journalists put their incomes and sometimes even lives at risk when reflecting them. What in their turn do the activists do to encourage and protect the journalists “with balls”?

This journalist narrowly escaped being fired

Sometimes “safety nets for journalists” are being discussed but personally I do not have experience with such networks. Rather, I know very well that NGO-supported and NGO – awarded are these journalists who work at the biggest media, which could offer a stage for not so uncomfortable activist messages.

The same problem examined from another angle points that great media stories are squandered because of lack of international activist cooperation. Here is one striking example. An “empire” of maybe 20 companies – coal mines, power plants, and district heating utilities – is owned by a shadowy businessman in Bulgaria. These firms are firstly privatized under suspicious circumstances, later registered in the Seychelles, and now owned by phantoms in the City of London. All of them are highly indebted, do not pay taxes, do not pay salaries regularly, have disastrous labor conditions, including numerous casualties in the mines, and on top of this they receive lavish “green subsidies” from the state budget.

There are some reasons why the authorities in Bulgaria turn their eyes away. But where are the reasons why the international activist community does not look concerned with this case? Because all we are preoccupied mainly with ourselves, we remain weak. And our causes remain weak.

No wonder that investigative journalists are so often prone to desperation. Every journalist constitutes his own army of one solider. The bridges to the mainstream zone are burned, and still nobody is punished. It can even happen that the tax sinners are uncovered only to receive praise as being smart. In such cases the deepest personal convictions are questioned. These journalists who find a reason to continue emerge stronger – but already not so enthusiastic to further collaborate with complacent activists.

The fourth mistake that activists make when campaigning on tax, finance, inequality and similar matters is to pay little respect to numbers. When economy and finance are concerned, one always has to have precise numbers, and the best case is to produce (calculate) them by oneself. In the field of business the messages supported only by emotions and abstract notions are simply useless. Even more, they are counterproductive.

While working as an editor in a reputable weekly magazine I have turned away (or have rewritten by myself) dozens of campaigners’ articles written very well but lacking numbers. To busy people like politicians and economists a text without numbers is not readable. When I am reading a new article I am firstly looking for numbers: is there something new to me? Only when the numbers are new and convincing I continue reading the conclusions.

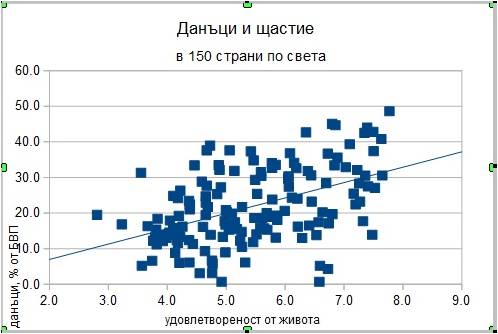

“Happy countries have higher taxes” or “The Pearson coefficient of 0.48 speaks of medium to strong correlation between…”?

There is also the opposite threat. I know that the journalists at Reuters have a stringent rule: never use more than two numbers in one sentence. If you have a lot of information that you want to communicate, better use graphs – of course, unpredictable ones.

Last but not least, a great deal of activists fail to understand that journalists are human beings. Here is a nice story. Lately I was invited to speak about media relations to some of the most experienced Bulgarian activists which had campaigned successfully against fracking, TTIP, GMO, and many other causes. The audience was well prepared and self-confident so I decided not to teach them, but instead asked about their general attitude toward journalists.

For more than one hour I heard so many times: “They are stupid”, “They are incapable to dig deeper”, “They are lazy”, “They are dependent”, “They are frightened”… I took the floor only to say: “They are human beings”.

There are only two types of journalists: those who think and those who don’t. Some activists may feel intimidated when engaging with the first type. They prefer to avoid tricky questions, and instead, have their messages repeated undistorted through as many channels as possible.

Merely a huge megaphone – is this really what activism needs most? People and organizations that are so deeply convinced in their correctness to suppress another points of view always look suspicious. No surprise that such activists are being punished sometimes by the most cooperative and benevolent yet used to thinking journalists.